We are proud to announce that Lindsey Dieter’s essay We Are What We Specify – first published in the launch edition of container – has been featured at Healthy Materials Lab (HML). HML’s mission is to develop, promote, and implement toxin-free building materials whilst simultaneously increasing the transparency of material composition for consumers and professionals alike.

HML is a partnership between Parsons Design Lab, Building Product Ecosystems, Green Science Policy Institute, Healthy Building Network, and Healthy Product Declaration Collaborative.

Read the full essay below:

The number of times you and your fellow American citizens have confidently declared these words at the dawn of a new year are innumerable:

“This year, I will prioritize my health.”

“This year I will eat nutritious foods that are good for my body.”

In reality it is irrelevant whether or not people follow through with their intentions. Why, you might ask? The firmly rooted priority within our resolutions is human health, most often sought through exercise and improved nutrition. Our resolutions do not take into consideration a larger issue — material safety and quality in our built environment. Why not declare that we will furnish our homes with flame-retardant free furniture? Or that we will choose VOC-free paint, eliminate vinyl flooring, wall and window coverings from our homes and acknowledge that a manufacturer’s unbeatable prices for their furniture are saturated with formaldehyde?

Chances are that, regardless of education or socio-economic status, the individual declaring a movement towards better health has no idea that the built environment is affecting their health at an equal if not greater rate than the foods they consume. We spend an average of three hours per day consuming food. Our organs digest and absorb the nutrients (or lack thereof) embedded within each meal. We spend twenty four hours per day in or near a constructed environment and our skin — the most porous organ in the human body — is actively absorbing the chemical composition of every material we encounter. Unfortunately, the rates with which we experience the effects of vinyl flooring or high-gloss paint amplify gradually over long periods of time, whereas a rapidly increasing waistline is tough to ignore. There are a variety of efforts that can be taken in the fight against toxic environments. The manufacturer, consumer and designer all have the power to shift society’s attitude towards holistic health. I will examine this challenge from the role of an interior designer, presenting a cross-examination of the challenges inherent in selecting both nutritious foods and safe furnishings. After all, we are both what we eat and what we specify.

In an attempt to simplify an inherently complicated subject, I will examine the lifecycle of two common items: an apple and household paint. We are likely to come in contact with both of these items on a regular basis and upon first glance, neither suggest a threat to the human body. Although the lifecycle of each varies considerably, there are commonalities in the production and purchasing process of both. The common folk phrase “an apple a day keeps the doctor away,” is widely disseminated, and largely believed to be true. A quick web search on “how to freshen up a room” will reveal a similarly innumerable and trusted list of paint colors and topical applications with which to do so. Taken at face value, both assumptions are incredibly misleading.

PRODUCTION

The apple harvesting season in New York State runs a brief sixty days (roughly through September and October)1. How is it, then, that we can enjoy this health enhancing fruit whenever our hearts desire, three-hundred and sixty-five days a year? The answer lies in Controlled Atmospheric Storage. Apples are stored in sealed rooms where oxygen is reduced by an infusion of nitrogen gas, from approximately 21% (the level in the air we breathe) down to 1-2%. Temperatures are kept at a constant 32-36ºF. Humidity is maintained at 95% and CO2 levels are carefully controlled.2 Sounds harmless, right? As an independent process, yes. However, the mixture of nitrogen with The US’s most commonly used pesticide is concerning.

The US Department of Agriculture (USDA) found that 80% of the apples sold in the United States are coated with diphenylamine, or DPA.3 DPA keeps your prized honeycrisp its picture-perfect pink after months of cold storage. Sorry, you didn’t think that was a miracle of Mother Nature, did you? DPA was banned by the European Union in 2012 which should be more than enough impetus for the USDA to reevaluate the 0.42 parts per million (ppm) — 0.32ppm higher than the allowable concentration — present in the 10 pounds of apples consumed yearly by the average health conscious citizen.

The hazmat suit at the dinner table is starting to sound like a pretty good idea.

Paint production will inherently involve a more extensive list of ten-syllable words than a honeycrisp apple. However, not all of them are toxic (just most of them). Paint is composed of colored pigment, resin, a solvent and additives. Naturally-occurring pigments are readily available in minerals, insects and botanics that can be harvested to color textiles and paint. Reducing a negative health impact is possible through the use of a limited color selection using natural pigments. To achieve a palette of 16 million color varieties, Pantone employs a complicated and potentially toxic chemical recipe. For example, the “King’s Yellow 39” feature wall you are dreaming of contains high levels of arsenic, and the “Cinnabar Red” master bedroom will introduce mercury into your after-hours routine.4 Producing a standard batch of paint involves an industrial blending process combining water, titanium dioxide (TiO2), resin and calcium carbonate (CaCO3).5 TiO2 is an occupational carcinogen that may cause cancer with prolonged exposure. Paint manufacturers adhere to strict health and safety protocols involving industrial fans for proper ventilation and respiratory masks to ensure none of the toxic chemicals present are inhaled during production. The average consumer’s ventilation protocol is likely much less thorough. Reassuring your client that a coat of paint will freshen up any room seems to lose its validity when the resultant disclaimer includes sporting a hazmat suit prior to enjoying the addition of Pantone 7523 C to the dining room — food for thought…

PURCHASE

Purchasing power is fueled by the informed consumer. An overwhelming array of products are available for the choosing and it is the responsibility of the consumer to use the tools available to them to make an informed decision. This is easier said than done. In the case of an apple, the option to purchase standard or organic produce is likely top of mind. The standard produce is cheaper, but the addition of pesticides is guaranteed. Organic produce may cost more, but in order to be certified as USDA Organic, farmers must produce a history of substances used in the last three years, pay numerous certification fees, pass crop and produce inspections and reapply for certification annually.6 Although soil leeching, acid rain and crop cross-contamination can dampen the accuracy of the USDA Organic label, the use of a single third-party certified governing body provides the consumer a high level of confidence.

Unfortunately, the same standard of information does not exist among the plethora of paint colors available at Home Depot. Food products are required to display both an ingredients list and nutritional information chart. Manufacturers of building materials are not required to disclose any of the ingredients in their products. The building material equivalent to a food products ingredient list is a Material Safety Data Sheet (MSDS). The MSDS must be made available upon request; however, the level of accuracy with which these sheets are filled renders the information nearly useless. A manufacturer can wash their hands of any obligation to provide complete product disclosure with a simple “proprietary information” statement. When you are fortunate enough to find a MSDS online, the majority of chemical ingredients are listed as complying with an outdated standard followed by an indecipherable numerical indicator. In an ideal world, the name and packing of a product would be informative enough for you to make an educated decision that is in line with your priorities. For example, ECOS Interior Atmosphere Purifying Paint sounds too good to be true. You mean I can freshen up the aesthetics and air in my living room simultaneously? Hardly. To aid in unlocking the proprietary secrets of our built environment, the highly trained team at Pharos has created an extensive database of both building products and chemicals. A single search can reveal a detailed contents list, hazard summary, lifecycle research and additional documents directly sourced from the manufacturer. Our too-good-to-be-true ECOS Interior Atmosphere Purifying Paint proved to do quite the opposite (Figure 1). The paint is composed with 20% TiO2 and 25.1% Oleic Acid, a compound on the German FEA Restricted Hazards List. The remaining ingredients are associated with gene mutation, developmental toxins, respiratory, eye and skin irritation, and persistent bio-accumulative toxins that will not break down once released back into the environment. The hazmat suit at the dinner table is starting to sound like a pretty good idea.

MOVING FORWARD

So with all of this information, where does the future of not only our good intentions but the health and wellbeing of society at large stand? First and foremost, there is no gain in sugar-coating the seriousness and complexity of this issue. We are facing an epidemic of rapidly decreasing societal health that cannot be taken lightly. Fortunately, the USDA is working in our favor when selecting the foods we put in our body. Who is on our side when determining the fate of the occupants within buildings? There is potential for change at every step of the design process. Manufacturer transparency will establish trust and drive highly toxic products out of production. Designers can implement a zero-tolerance policy for the use of chemical-laden materials into designs. Contractors can verify that all products entering a job site are supporting the health of future occupants. We have the creative capability to innovate in both the specification and design of material systems that are not harmful to the human beings at the core of our work. If the design is lethal, aesthetics are irrelevant. Unless designers everywhere are interested in introducing an occupant waiver form into their design brief, it is of the utmost importance that we do the research, specify accordingly and educate.

TIPS

- Look to reputable designers who are creating incredible spaces that are not harmful to the environment. You don’t need to re-invent the wheel; you just need to refine the options available when you spin.

Select no VOC paints in a color palette derived closely from what nature does well already. This doesn’t translate into a granola infused interior, but the vibrant neon-blue is likely out.

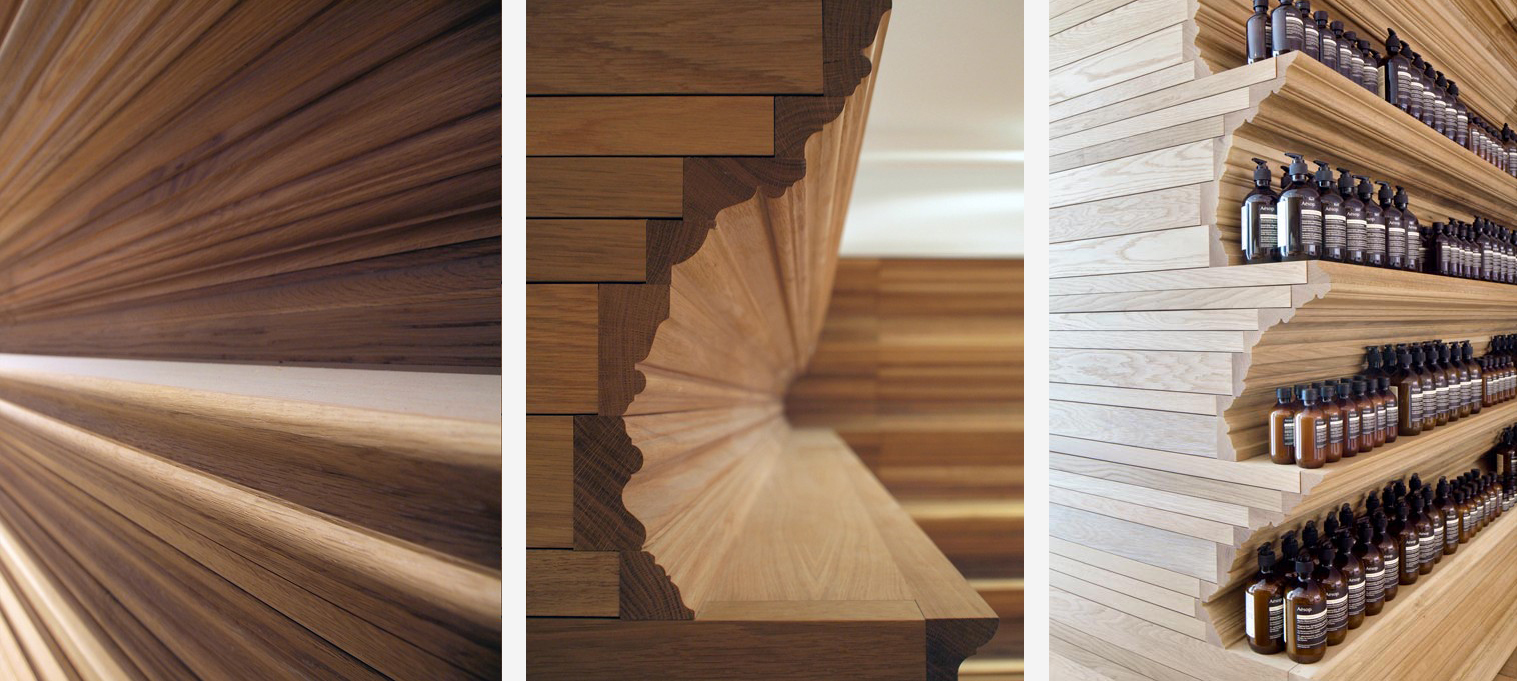

Innovate in material applications. Introduce plaster onto vertical surfaces, experiment with textiles for acoustic barriers and engage in the versatility of simple materials.

Use solid wood furniture and water-based paints and stains.

Look to trusted third-party certifiers like Green Guard, Pharos, The Forest Stewardship Council and LEED. Mandate that manufactures provide you with both MSDS and Healthy Product Declaration Act (HPD) information. If the manufacturer doesn’t know what an MSDS or HPD is, educate accordingly.

Avoid products with brominated flame retardants, phthalates, harsh sealants and polyvinylchloride.

Finally, sleep soundly knowing your careful consideration in specifying materials and finishings is not only shifting the market towards the production of healthy building materials but is protecting the health and wellbeing of everyone.

LINDSEY DIETER

NOTES

1 : NEW YORK HARVEST, accessed January 2015, http://www.pickyourown.org/NYharvestcalendar.htm.

2 : Rackley, 35 – 40.

3 : APPLE CHEMICAL COMPOSITION, accessed January 2014, http://rt.com/usa/154676-us-appkes-chemical-ban/.

4 : Smulders, et al., 47

5 : PHAROS Project. http://www.pharosproject.net.

6 : USDA, accessed January 2015, http://www.usda.gov/wps/portal/usda/welcome.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Smulders, S., K. Luyts, G. Brabants, L. Golanski, J. Martens, J. Vanoirbeek, PH Hoet, “Toxicity of nanoparticles embedded in paints compared to pristine nanoparticles, in vitro study.” Elsevier Ireland Ltd 2014.

Richard Jones, “Soft Machines.” Oxford University Press, 2004.

Rackley, Stephen A., Carbon Capture and Storage. Boston : Butterworth-Heinemann/Elsevier, 2010.

PLATES

Figure 1: ECOS Interior Atmosphere Purifying Paint, https://www.pharosproject.net/

![Precedent for Type C LAYER CAKE / LOFT (LIVE-ADJACENT): Maison de Verre [Paris, France 1932] by Bernard Bivjoet and Pierre Chareau, consisting of ground floor consulting rooms for a doctor with two floors of living accommodation above.](http://sce.parsons.edu/container/files/2014/12/Maison-de-Verre-300x235.jpg)